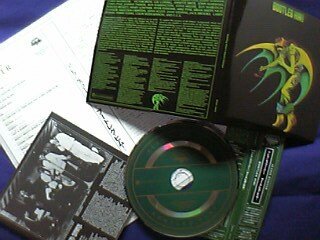

limited "Bootleg Him!" only in Japan (Dec 2005)

This is from the inner sleeves of Japanese limited edition of “Bootleg Him!”

Rolling Stone, July 8th, 1971

“Alexis Korner, Father Of Us All”

By Andrew Bailey

Queensway, between the West End and Notting Hill, is a comfortable family area, not the place for superstars to live. Sitting on a plastic sack filled with foam particles in the living room of his maisonette, Alexis Korner looks like he invented the better end of Kings Road. Clothes and furniture are the only flash images Korner allows himself. His two boys, Damian and Nicholas, join in the conversation, very self-possessed and charming.

The night before, Alexis had played a solo date at the concert hall in Bristol. “It was the first concert I’ve actually enjoyed playing in England,” he said. “The audience worked with me. It was the first time in ages that I’d seen an English audience actually understand that you work with a performer to get the best. You don’t sit back and say, ‘I’ve paid my 15 bob, now gas me’, which has been the British vice for some time.”

From his position at the center of a genealogy of contemporary British music, Korner can look out at a complex universe of musicians and movements which have been influenced by him. On the outer limits are Led Zeppelin and Jesus Christ-Superstar. Packed close in orbit are the Rolling Stones. Mick Jagger and Keith Richards sat in with Korner’s band Blues Incorporated, when Charlie Watts was the drummer.

And then there’s Jack Bruce, Ginger Baker, Graham Bond, Lee Jackson of the Nice, Led Zeppelin’s Robert Plant, Terry Cox of Pentangle, Manfred Mann’s Paul Jones, Andy Fraser of Free, Victor Brox, and Long John Baldry. On the jazz side there are a score of musicians who spent time with Korner but whose names mean little outside the tight British jazz scene, except perhaps for Dave Holland, bass player with Miles Davis; Alan Skidmore, who have both since achieved recognition in Europe.

They all found in Korner a warm refuge of emotional stability and respectability at a time when the environment wasn’t ready for their music.

Korner is probably as far removed from the classic blues background as is possible. His father was a cavalry officer in the Austrian Army during the First World War. His mother was Greek-Turkish. After being shuttled between relatives in France, Switzerland and North Africa, Korner settled with his parents in France. They left on one of the last refugee ships when France fell to Germany at the beginning of the Second World War.

“War at that age,” Korner remembers, “was pretty marvelous, romantic for an 11-year-old boy. Just super fireworks. And if you see a few dead bodies, they don’t look like bodies. Just one of the images you have of glamor and honor at that age.”

“My father was 58 when I was born, and he was already getting tired. I can only remember odd things about him. He used to tell me about the Russian Revolution. He’s been through a great deal of that. And I remember him describing Caucasian yogurt … you grab a knife and cut it up in chunks, that sort of thing.”

His father was of the old Viennese school. He expected to be entertained by the whole family, though he didn’t play an instrument himself. “I had piano lessons from the age of five,” says Korner. “I played OK, but my father really was convinced that I should become a virtuoso violinist, who would never, of course, dream of becoming a professional. A brilliant 19th century dilettante was what he wanted.

“It was in 1940 that I came across a record by Jimmy Yancey. I can’t say how important that record is. From then on all I wanted to do was play the blues. Blues and jazz pulled me away from what was left of my family. I was brought up in the latter part of the war by my mother’s family. They were ship-owners, that sort. People I don’t get on with at any level, I don’t like their reasons for living, I don’t like their objectives, I disagree with their means of getting there. The only thing that saved me from becoming like them was this music. And that record gave me a way out of it all.”

“You start campaigning for things and, you know, you say we’re going to make blues into a big music and this that and the other …”

Korner couldn’t have chosen a worse time to try and sell the gospel. It was just a few years after the war. In Britain, there was still rationing of food. The mood favored the radio big bands, crooners, a little jazz, the pretty gimmick ballad singer.

“You felt OK about that,” said Korner, “because you knew you were right. And all the cats, when we worked together, we always knew were right.”

“At the same time as we felt this almost missionary thing, we were also completely without any sort of aesthetic worry about it; we weren’t giving up anything for our kicks and everything else that went with them at the same time. So it wasn’t quite missionary zeal. If you like you were serving God and man at the same time and enjoying both.”

“During the war we lived in a place in north Ealing in London which had a clubhouse where there was a piano and two or three of us used to play boogie woogie. A lot of the people who I played with early on, like Chris Barber, were record collectors and to whose house one would go to sit down and play guitar and things. Just mess-around with the music – it was pretty specialised. Nobody bugged us, no one was in the least bit interested in us, not the slightest we weren’t considered a market. Teenagers didn’t exist at that time.”

“In those days between the ages of 12 and 18 you meant nothing. You were the extra place at the side table if someone came to dinner. You were too big to be petted and fondled or thought pretty and you were too small to work and you were of no interest to anyone, and you had a chance to learn – this is what’s missed today. If people had started looking at me under a microscope at the age of 13 I think I would have collapsed. Teenage markets and pressures and finance and everything like that, I couldn’t stand all that. I’ve had enough of a job coping with it at the age of 43.”

“I suppose basically I had always intended if it were possible to make a living out of playing blues. But I never admitted it to myself. Because I don’t suppose I could have given a logical reason for it ever becoming possible to do so. I wanted to be able to play guitar, I wanted to be able to make music hurt.”

“I can’t explain why one wants to pass a particular sort of pain onto other people, but you do – without asking why you do it. I say I’m a compulsive musician, but it’s also a bloody good way out of having to do anything else.”

In the late Forties, Korner had a blues quartet inside Chris Barber’s Jazz Band, which played about half an hour a night on band gigs.

“It had a very bad five-piece rhythm section which consisted of guitar, banjo, piano, bass and drums. I was only in it because I played in the break-off group. It’s like the singers in the old Palais bands who used to be given rubber-stringed guitars and sat in the rhythm section, completely inaudible. They stuck me next to the banjo, and an unamplified guitar next to a banjo doesn’t sound like anything.”

“But I couldn’t quite get in with that after a bit because I happened to like Charlie Parker as well as Joe Oliver and it made it a slightly difficult situation in the Barber band because at that time it was very, very traditionally minded. You did not mention people like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie and that area of musicians. You talked about Johnny Dodds and you talked about Louis Armstrong and you talked about Joe Oliver. I loved Bebop, as it was then a great blues feeling in it.”

“We played very small grotty clubs, because that was the only place you could get jazz bands into. And I was considered as a jazz man rather than as a blues player. Because there were no blues players – you played one sort of jazz of another sort of jazz. And I began to get worried about that because I didn’t feel I was a jazz player, and the reason I didn’t feel I was a jazz player was because to me setting moods was more important than improvising. And if the same phrase in the same place created the right effect, I was perfectly prepared to use it every time. I wasn’t worried that I wasn’t improvising.”

“To me, that is the basic difference between the two. A jazz man needs to express himself in terms of sound, he must be identifiable from other jazz men. But in blues, if you find the right sound I feel it’s justifiable to keep it exactly the same every time, because it’s the overall mood you’re creating that’s more important than personal improvisation.”

When the British traditional jazz band leader Ken Colyer came back from New Orleans in 1952 and asked Korner to form a skiffle group, Korner said yes and found himself back with trombonist Chris Barber who joined forces with Colyer. Korner was the extra member once more, this time as the extra skiffle musician. Another member was Lonnie Donegan. The public rush for tea-chest basses and washboards was on. Britain had its first pop craze. Its very own. The American domination of the charts was broken. In the mid Fifties London alone sprouted an estimated 600 skiffle groups.

A track, “Rock Island Line,” from the Barber bands’ first album was a hit in America and then in Britain. Skiffle clubs opened and a purely British pop sound evolved for perhaps the first time. There were other effects.

“People are being unfair if they look back on skiffle too frivolously,” said Korner. “Every musical movement that is big enough, a popular movement, has got to produce some good musicians who wouldn’t have had the incentive to start playing without it.”

“It produced the Vipers, the first Colyer-Barber skiffle group, it produced Donnegan, Nancy Whisky, it produced such horrors as ‘Don’t You Rock Me Daddy-o’ and ‘Sail Away Ladies.’ It had a lot to do with producing Tommy Steele and that entire area … Tin Pan Alley came up through the skiffle, very much indeed. It produced Big Jim Sullivan (now playing with Tom Jones) who had never played the guitar and would never have bothered to had he not come up in skiffle.”

“And it helped bring blues players from the States. People started hearing songs by Leadbelly and Big Bill Broonzy. And then they started singing Broonzy songs. At that time the interest in Negro folk music wouldn’t have been enough to bring over even cheap blues players. So skiffle can also be thanked for being the basis of the blues movement. Long before the R&B movement got going here the blues players had been coming over through skiffle. In the end the skiffle purists wandered away and the ground was paved for the Mersey boom and for R&B.”

It was Chris Barber – who had helped create the Trad craze – who finally put it down by bringing over American electric blues players like Otis Spann, John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters. Till that time the only blues following in Britain was for the folkier artists like Leadbelly and Broonzy. Barber gave Korner a spot in his band for the third time, this time playing electric blues. Cyril Davies, the harp player, was another member.

In the begging of the Sixites Korner formed the first Blues Incorporated and Thursday nights at the Marquee in Soho, then home of the National Jazz and Blues Federation, became the home of British R&B. Jack Good produced the first album, from a live set at the Marquee. There wasn’t too much challenge from American R&B on disc. It wasn’t until 1964, for instance, that the Chess label with Chuck Berry was issued in Britain.

“There was still a purist feel around,” says Korner. “It wasn’t intended, but I suppose that sort of missionary thing about popularizing jazz was very strong cause we always had a very high proportion of jazz men in the band. Ginger Baker was a jazz player, so were Dick Heckstall-Smith, Graham Bond and Johnny Parker. From different schools perhaps, but all jazz players.

“We all felt that jazz could be popular music if it were properly presented. That hasn’t really ever happened. Most of the British jazz musicians have killed it stone dead, by perpetuating its exclusiveness. In time, many of them found they couldn’ make a real living here, and they mostly went abroad.”

“Technically, Blues Incorporated was the first professional British blues band. We were playing electric stuff by then and Cyril and me were getting thrown out of perfectly respectable jazz clubs for doing so.”

Cyril Davies split from Korner and formed his own band, the All Stars. From then on Blues Incorporated was kept fresh with a steady infusion of personnel. Anyone who was around joined when they could. Eric Burdon, Long John Baldry, Ronnie Jones (a black GI), Paul Jones. There was a “nervous” Charlie Watts on drums, Dick Heckstall-Smith on saxophone, Jack Bruce on bass. And for six months in 1961, Mick Jagger.

“Mick got in touch with me at the start of the blues scene. He wrote me a letter and sent me a tape of some stuff he’d done, and he became a founder member of the first professional, or three-quarters professional Blues Incorporated. The first skiffle EP record that I made was called skiffle, but I didn’t want it to be called skiffle. We weren’t a skiffle band, we were a blues band, and we had many rows with Decca but they still insisted on calling it skiffle, but the second EP they agreed simply to call Blues Incorporated. By the time Mick got in touch with me, Cyril Davies and I had been playing blues stuff up at the Round House, a pub in Soho, which we’d got going as the London Blues and Barrel House club for a couple of years.”

“Charlie was still working in an advertising agency, he was too scared to go pro with us, so we started auditioning drummers and we got Ginger in instead of Charlie, and it was shortly after that when Cyril and I agreed to part company. Bondy [Graham Bond] came in to replace Cyril. We played Rome, we played all sorts of places. Then the band changed, of course, as it went along.”

“It developed into what was the strongest jazz rock and roll reed section that’s ever played here – Heckstall-Smith and Bondy, who wasn’t playing organ then.”

Ginger Baker also left, and Phil Seaman came in. “People say that Seaman’s hangup is that he looks so much like Ginger. I’ll tell you what Ginger’s real hangup was, everyone used to say he looked like Phil Seaman. It’s a sign of the times. Phil Seaman was the major jazz drummer when nobody knew Ginger, and jazz was a much more popular music in England 10 – 15 years ago than it is now. It was practically a pop music, you know. Jazz drummers won Melody Maker polls, jazz singers won polls. Jazz groups were pop groups, and Phil Seaman was a national musical figure.”

“The band kept changing and replacing itself, and I dissolved the band eventually because, after many, many years, I found I had nothing more to say with the band.”

Nearly everyone who passed through Blues Incorporated became established in their own right. An exception was Duffy Power, who has faded out almost completely.

“Duffy was greatly admired by a few people, and has always been dreadfully ignored by everyone else. He has always been for me a major performer. Duffy is one of the most important singers ever to have worked here, and I include American singers as well. A major singer and writer. He’s very very difficult to keep up with. I tried four or five times. Then he wouldn’t get up any more in the morning to make the gig, so what can you do.”

“Commercially, Blues Incorporated was at its peak in 1962 when we played the Rothschilds’ ball and all that sort of stuff. I’m sure that one of the reasons why so many great musicians chose to work with me was because there was simply no alternative. There wasn’t another R&B band that played regularly twice a week to at least a thousand people. But we never thought of ourselves as being popular, in the sense that the Tremeloes or some group like that is. We didn’t play the pop ballrooms and so I don’t think that the development of pop music had much to do with us.”

A lot of Korner’s purist followers thought he’d had an aberration when he decided to lead the house band on a children’s TV program called 5 O’clock Club. This was after Korner’s band had been the backing group on Gadzooks!, one of the first British rock and pop TV series. “5 O’clock Club was very important,” said Korner, “because we made more converts through it than through all the specialist gigs put together. But in a way, it turned out to be the kiss of death as well; one, because people assumed that as we were doing television we were too expensive, and two, because once you became associated with a children’s show you’re finished anyway.”

“We kept the trio going out of the band. Danny Thompson and Terry Cox and myself used to play a lot of gigs up and down the country.”

It was around this time that Korner, using his broadcasting experience, started to sing as well as play guitar. He cut his first singing album, New Generation of Blues in1968. The band once more became a cult and musicians would arrive at gigs for occasional sessions. One was a Birmingham singer, Robert Plant. He toured with Korner around the club and university circuit before being picked up by Jimmy Page to join Led Zeppelin in California. He didn’t get to finish an album he was cutting with Korner and Steve Miller, though some of the completed tracks will be included in an anthology to be released later this year which will also contain songs with Charlie Watts, Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce. For a while Korner led another trio, called Free At Last.

In the spring of 1968, Korner toured Denmark with one of that country’s leading blues outfits, the Beefeaters. Korner and the lead singer, Peter Thorup, then formed their own group, New Church.

“At one point my daughter Sappho was singing, Nick South was on bass, and it shifted around a lot, but there was always Peter and I. On the last tour we did as a band, we used Zoot Money on piano and vocals. We were doing a lot of gospel stuff, and we changed the sound around, sometimes it was a very bluesy tour, sometimes jazzy. One quartet which recorded a very good live album, one live side at a concert in Hamburg in December of 1969, was Ray Warleigh and Colin Hodgkinson and Peter Thorup and myself.”

“That particular concert was practically a climax of what it possibly the best tour musically that I’ve ever done in my life, and it has a very strange ethereal quality for me, because it was the most tremendous bit of personal communication that I’ve ever had with 2000 people. We had them all sitting on the stage because there was no room in the audience and we let them smoke, which in a German concert hall is absolutely out of question.”

Brian Jones heard about what Korner and Thorup were doing in New Church and after leaving the Stones he asked to join. Korner persuaded Brian to follow up his interest in Moroccan music and a switch to the saxophone. They worked together selecting musicians while New Church rehearsed at Brian’s country estate. New Church made its London debut at the Stones concert in Hyde Park in July, 1969. The performance turned out to be a tribute to Brian.

Korner’s voice, hoarse and rumbling, is familiar to nearly everybody in Britain. Not through his singing but as the persuasive voice on scores of TV commercials, as well as on radio as a host and interviewer. A few would recognise it from C.C.S., a big band of musicians that Mickie Most assembled.

“When I look back and reflect on how things have changed I can’t help but laugh. Years ago I wanted to play Chuck Berry songs with jazz musicians but they thought it was inferior. And then I wanted to play Motown with blues players but they thought it was demeaning, so it’s only now that I’ve had a chance to play pop.”

“I must have been heavily schizophrenic all my life. The me who hears what the other me can’t play is the dominant one. I guess music, particularly the blues, is the only form of schizophrenia that has organised itself into being both legal and beneficial to society.”

Along with John Mayall, who in 1962 formed the first Bluesbreakers after being shown by Korner that blues bands could be viable propositions, Korner can look back and see what has happened in British blues. He doesn’t believe there has emerged a proper British form of blues. “I suppose the parallel development in American blues to the British movement has resulted in Johnny Winters. The British feel of blues has been hard, rather than emotional. Far too much emphasis on 12 bar, too little attention to words, far too little originality.”

Korner had made his next big decision. He’s preparing to go to America for the first time. “I’ve never been before,” he says, “because I was scared. Since the age of 12 all my musical thinking has been influenced by Afro-American music, so it’s not a casual decision to make. I had to wait until I was good enough, had reached a standard of communication which would serve as a reasonable starting point in America. Now I am ready to risk it.”